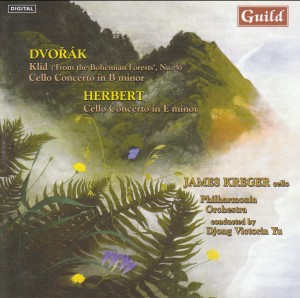

| DVOŘÁK, Antonín (1841-1904) | |

| 1. | Klid / Silent Woods / Waldesruhe / les bois silencieux (from "The Bohemian Forest"), | 6:45 | |

| CONCERTO FOR CELLO & ORCHESTRA, Op. 104 (B Minor / h-Moll / si mineur | |

| 2. | Allegro | 6:08 | |

| 3. | Adagio ma non troppo | 11:56 | |

| 4. | Finale: Allegro moderato | 13:10 | |

| HERBERT, Victor August (1859-1924) | |

| CONCERTO No. 2 FOR CELLO & ORCHESTRA, Op. 30 (E Minor / e-Moll / mi mineur) | |

| 5. | Allegro impetuoso | 8:02 | |

| 6. | Lento-Andante tranquillo | 7:50 | |

| 7. | Allegro | 6:37 | |

The Works

The three works on this recording are bound by the sort of complex network of interconnections that a skilled novelist delights in creating. At the center of their story is the remarkable odyssey that brought Antonín DvoÍák to New York to serve as Director of the National Conservatory of Music of America between 1892 and 1895.

DvoÍák would never have accepted this post but for the persistance of Jeannette Thurber, the conservatory’s chief patron and guiding light. Determined to put a world class composer at the head of the institution, she bombarded DvoÍák with telegrams month after month, brushing aside his repeated refusals. After DvoÍák at last signed her contract in December 1891, he immediately planned to make a farewell tour of his Czech homeland, performing as pianist along with violinist Ferdinand Lachner and cellist Hanuš Wihan (the three visited thirty-nine cities and hamlets). For the central offering on their programs, he had a score ideal for mixed audiences-his recent Dumky Trio (Op. 90), cast in easy-to-grasp lyric forms-and his catalogue also contained several works to showcase the violinist, but he badly needed cello-piano music as well. On Christmas day, he began remedying this gap, writing a Rondo for Wihan. He then transcribed one of his Slavonic Dances for cello; and on December 28, he turned to his collection From The Bohemian Forest, Op. 68, a group of six piano duets completed in early 1884, and made a cello-piano arrangement of No. 5, entitled Klid ("Silent Woods"). Wihan and the composer duly premiered Klid on January 3, 1892, when the tour reached Rakovnik. Further adventures awaited DvoÍák, however, before he would pen the final orchestral version heard in this recording.

Arriving at the Conservatory in the fall of 1892, DvoÍák found that one of the stars of his faculty was the leading cello instructor: a man who shared his central European musical grounding, but differed greatly in social orientation. For, if DvoÍák’s origins ensured an unbreakable attachment to his native land even after he had become world-famous, Victor Herbert’s background prepared him to cross border after border, eventually becoming a naturalized American with no qualms about severing older ties. The Dublin-born son of an Irish painter, Herbert was brought to England by his mother at age three, after his father died. The widow Herbert then made a second marriage, with a German physician, and the family settled in Stuttgart, where the boy received a thorough musical education. Herbert was already embarked on a solid if modest European career as a cellist-composer when, in 1886, he and his soprano wife joined New York’s Metropolitan Opera company-he as principal cellist, Mrs. Herbert as a solo singer. When DvoÍák arrived in America, Herbert had already left the Met and was serving as Assistant Conductor of the New York Philharmonic under music director Anton Seidl, simultaneously pursuing a busy career as a free-lance solo and chamber-music cellist.

Mrs. Thurber hoped DvoÍák would strive to foster the development of a distinctively American school of composing. Hearing American folk music (particularly that of Black and Native Americans) fired the DvoÍák’s enthusiasm for her vision, and during the first months of 1893 he produced an exemplary work for American composers, embedding ethnic traits into his Ninth and last Symphony (Op. 95), subtitled From the New World. Assured of a prompt performance by the New York Philharmonic, DvoÍák gave the score to Seidl-which meant that his assistant, Herbert, was one of the first to see it.

This Symphony, and its triumphant premiere on December 16, may have spurred Herbert to seek a Philharmonic success on his own more modest terms by writing a cello concerto (his second) to play with the orchestra. Significantly, Herbert set the concerto in E minor, the same key as the New World Symphony, and some of the more dramatic gestures in his score are stylistically akin to DvoÍák’s idiom.

DvoÍák, as it happens, also now became involved with concerted cello music-a genre he had long rejected. In youth, he had essayed a cello concerto but did not think the results worth orchestrating; and more recently he had refused Wihan’s requests for a concerto on the grounds that the cello was unsuitable for an extended solo role. In the fall of 1893, however, Wihan asked him by letter to orchestrate two of the pieces he had written for their aforementioned tour, and DvoÍák obliged shortly before the New World’s premiere, completing the scoring of Klid on October 28. This may have given him second thoughts about a full-scale concerto, and historians conjecture that the acclaimed premiere of Herbert’s Cello Concerto No. 2, Op. 30 on March 9, 1894 (featuring the composer as soloist with Seidl conducting the Philharmonic) persuaded DvoÍák that the genre was viable after all. What is more certain is that DvoÍák gained familiarity with Herbert’s score and replicated some of its most attractive features. He was evidently impressed by passages that demonstrated Herbert’s capacity-rare among cellists-to make his instrument sing with introverted serenity in an extremely high register. Similar lyric flights in stratospheric pianissimo are quite prominent in the DvoÍák Concerto, and these, moreover, often exploit the same unusual key-color-B major-that Herbert chose for his own slow movement.

DvoÍák vacationed back in his homeland that summer, and it was not until the next conservatory term was well underway, that, on November 8, 1894, he began composing his Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104. By then, America had lost its magic for him. Homesick and physically out of sorts, he increasingly resented the separation from his family (only one of his six children had returned to New York). It irked him, moreover, that a substantial portion of his previous year’s salary still remained unpaid: the Thurber family business had gone under following the Panic of 1893, and Mrs. Thurber was having trouble meeting her charitable commitments.

Venting his most intimate personal concerns in the Cello Concerto, DvoÍák found no room for the Americanims he had employed the previous year in the New World Symphony, the Sonatina, the American Quartet, and the E-flat String Quintet. The result was a dramatic score tinged by tragedy and continually informed by heartrending melodic beauty-a work that towers above all other Cello Concertos in the Romantic repertory. While working on the slow movement, DvoÍák received news from Prague that his beloved sister-in-law (whom he had courted passionately in his youth) was seriously ill. In response, he embedded a theme (modified) from a song of which she was particularly fond: his "Lasst mich allein," Op. 82, No. 1 (composed in 1887 to a German text). DvoÍák completed the Concerto on February 9, 1895: the last music he would write in New York except for preliminary jottings toward a string quartet. On April 16, he left America, never to return (by then, Victor Herbert had also embarked for his own true music homeland, composing the first of the enormously successful operettas that would make him world famous).

In June 1895, DvoÍák’s sister-in-law succumbed to her illness. This tragedy inspired the composer to revise the last movement of the Cello Concerto, inserting a radiant, elegiac coda of some sixty measures in which the "Lasst mich allein" theme intertwines with echoes of the first movement. DvoÍák decided to premiere the piece in England on March 19, 1896, himself conducting the London Philharmonic with the British cellist Leo Stern. Curiously, Wihan did not take the piece into his repertory until 1899.

Although we do not know if Herbert’s Second actually convinced DvoÍák that the cello could be a persuasive concerto instrument, there is no doubt that DvoÍák’s score had precisely that effect on Brahms. Reading it over with mounting enthusiasm, Brahms confessed that, had he known such a cello concerto was possible, "I’d have written one long ago." Indeed, to this day, the piece remains the Romantic benchmark by which cellists are judged.

Klid, which, in effect served DvoÍák as a preface to his Cello Concerto, also introduces it on the present recording. The rapt, hushed opening melody reveals an almost symphonic breadth and flexibility as it unfolds, supported by subtly dovetailed fragments of countermelody. A central motif suggesting hunting-horn repeated notes proves a source of some emotional conflict. Wisely, DvoÍák curtails the reprise of the calm initial theme, and all tensions are resolved when the repeated-note figure achieves tranquility near the close.

DvoÍák immediately establishes the symphonic scope of the Cello Concerto by providing a full-scale orchestral ritornello in the classic manner. The principal theme, pregnant with the promise of adventure, quickly turns from brooding to rage, while the heart-on-sleeve lyric affection of what Sir Donald Tovey termed "one of the most beautiful passages ever written for horn" launches the second subject. In an extraordinarly compelling solo entrance, the cello imperiously transforms the main theme into a larger-than-life oration (DvoÍák risks the red-hot color of trombones in the accompaniment). Later, when the cello descends from the stratosphere to take up the second subject, the horn theme seems tailor made for it. DvoÍák’s development section results in a singularly effective formal twist. After mysterious orchestral first-theme discussions, the music reaches a distant minor key. Here the cello re-enters to keen a slow, doleful version of the main theme, which lamenting woodwinds then further transform into an entirely new melody. After these evolutions, it would be psychologically false to return to the theme in its original form for the reprise; accordingly, DvoÍák begins the recapitulation with exultant orchestra chanting the second subject. The main theme is thus fresh and welcome when it reappears in a coda that ends in jubilation.

A bucolic idyll sets the tone for the slow movement, and DvoÍák recaptures its calm after tragic outbursts in the central portion. A highlight is an eloquent accompanied cadenza that spills over into a peaceful coda. DvoÍák typically requires a great many themes for his finales, and this Concerto is no exception. The opening melody suggests heroic derring-do, but after a militant climax the cello allows the hero’s emotional vulnerability to peep through his bravado. Further contrasts are provided by a rocking interplay between clarinet and cello, and, later, by a fervent, folk-like melody. As in the first movement, DvoÍák ingeniously abbreviates traditional form, for the latter melody, appearing in solo violin, suddenly reveals that we are in the home stretch of the story. In the luminous coda, a "glorious series of epilogues" (Tovey), DvoÍák meditates upon his youthful passions with wisdom and tenderness, before heroism finally reasserts itself.

Although Victor Herbert’s adroitness is on a far lower artistic plane than DvoÍák’s mastery, his Second Cello Concerto is a period piece of undeniable charm, skillfully and gratefully written to emphasize the instrument’s most appealing songful qualities, and unfailingly euphonious in its tidy packaging of heart-on-sleeve Romanticism for safe domestic consumption. Following a layout favored by many Romantic composers of modest-sized concertos, it consists of three movements in one: its initial section is neither highly developed nor formally rounded off, but instead veers into a slow episode which functions as a central movement. A bridge then leads to a third movement, which recapitulates and develops first-movement material in tandem with vigorous virtuoso gestures.

Almost all of the opening Allegro impetuoso grows from two very brief, thematically related motifs, presented at the outset as an ardent imperious "question" in lower strings interrupted by a militant "answer" in violins and winds, the question and answer then immediately being repeated. The first solo episode is based on the question; the second, introducing a faster tempo, expands the answer; and in the unfolding narrative, both motifs undergo chameleon-like changes of mood-just as a single pair of actors with compendious wardrobes might set about portraying a full cast of characters.

Eventually, a quiet solo passage in high-register harmonics initiates a bridge to the Andante tranquillo slow movement. This is in A-B-A form, its outer portions serenely tuneful, its central section ranging from agitation to rapt meditation. An especially felicitous passage is the lushly orchestrated return of the A-theme in divided high-register violins.

The third movement returns to the tempo and mood of the opening. After some recapitulation and a cadenza, Herbert’s clever artifice combines the theme of the slow movement (cello) with the opening "answer" (orchestra) in an energetically flowing passage. Cheery transformations of the opening motifs are then presented in cannily contrived superimpositions and interspersed with scherzo-like solo passagework, and a final statement of the "question" brings a confident conclusion.